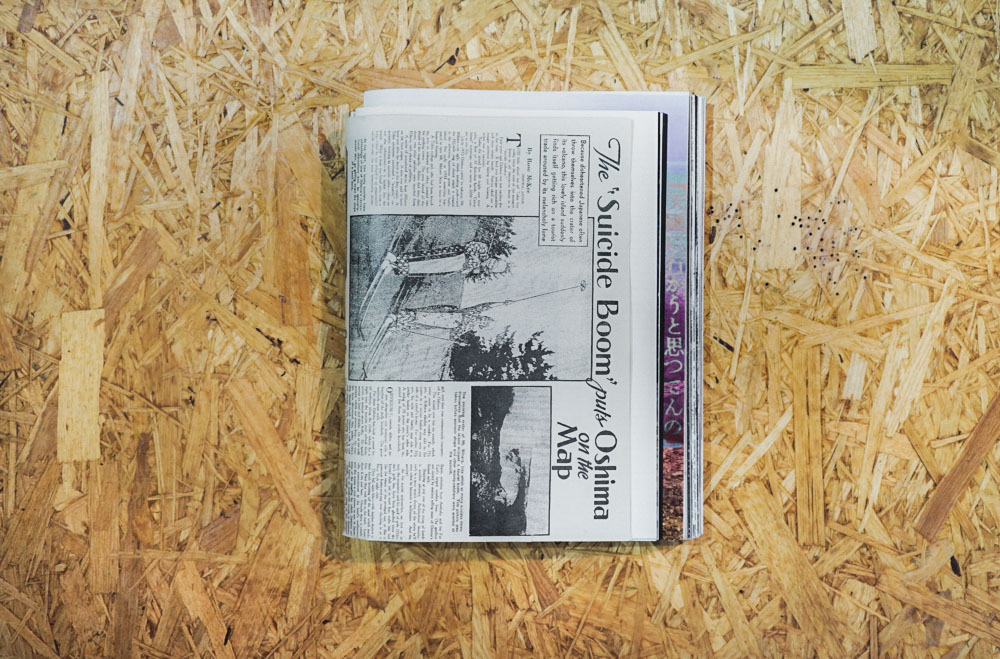

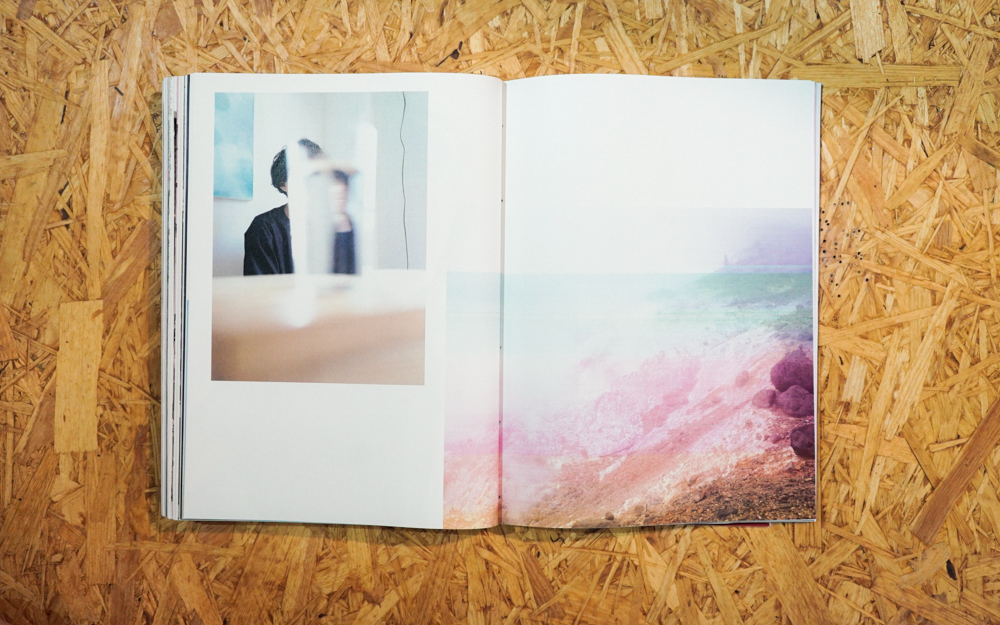

Kenji Chiga’s Artist book “The Suicide Boom” SOLD OUT! THANK YOU!!

SOLD OUT!

RPS is now ready to take online orders for Kenji Chiga’s artist book, “The Suicide Boom”.

千賀健史 写真集「The Suicide Boom」 from REMINDERS PHOTOGRAPHY STRONGHOLD on Vimeo.

“The Suicide Boom” SOLD OUT!

Book: 444pages

Languages: English and Japanese edition

Size: 262mm × 203mm x 25mm, 830g

Edition Number: 58 editions only (all made to order) all signed and given the edition number by the artist

Photo / Collage / Edit / Print / Bookbinding : Kenji Chiga

This project was realized in collaboration with BredaPhoto.

The book concept, storyline and art direction by Yumi Goto

In collaboration with Reminders Photography Stronghold, 2018

“The Suicide Boom”

In August, 2011, my friend disappeared. He was found two weeks later. During those two weeks, he was visiting places called “famous suicide spots”, such as the Aokigahara “Sea of Trees” and Tojinbo. 23 years old at the time, he was looking for a place to die. He seemed to be recovering afterwards, with the support of friends and family, but, in the end, he left this world in August, 2015. Without talking to anyone, and leaving nothing. The way he took his life was by a suicide method which was often talked about at the time. Would that have not happened had he not known that method purported to provide a painless death? At the least, would it have delayed him a little bit more?

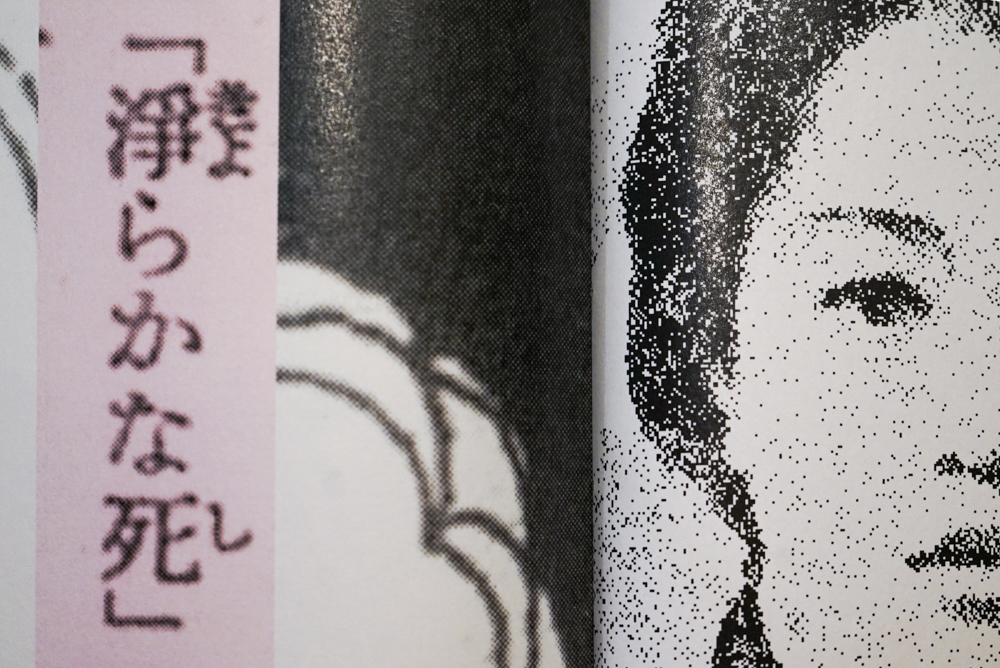

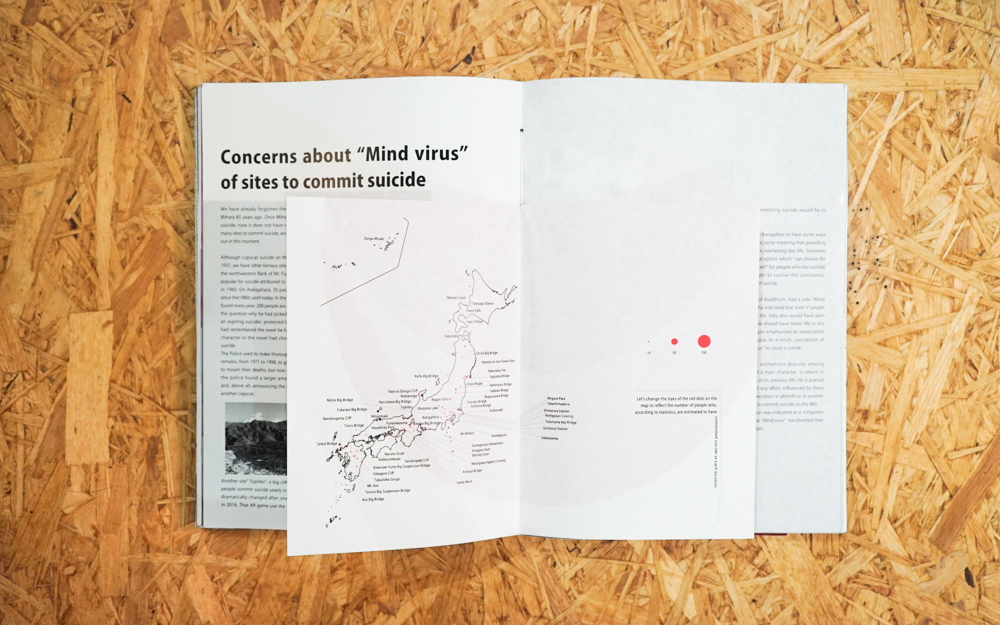

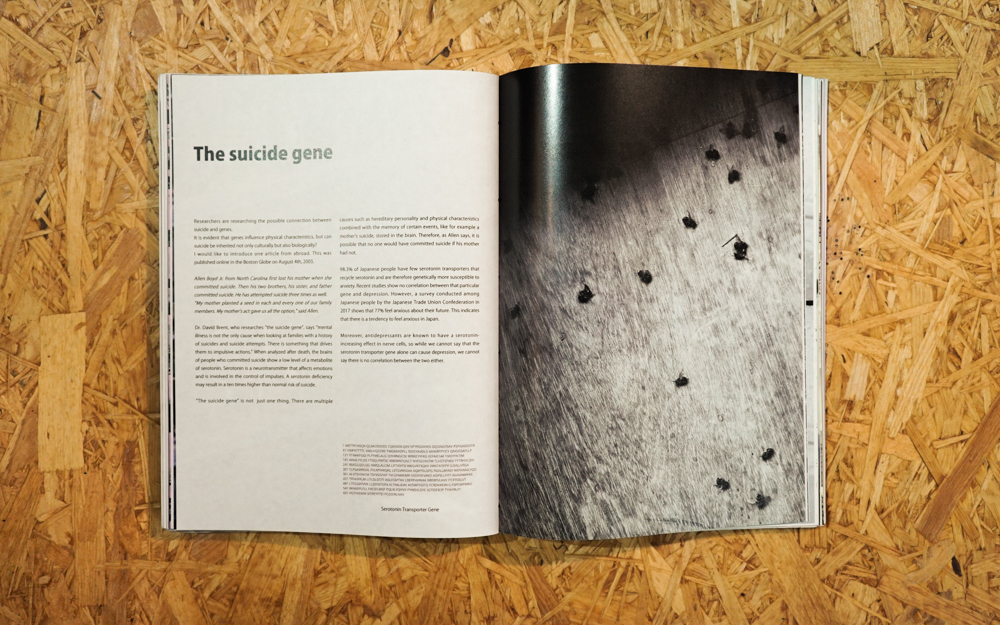

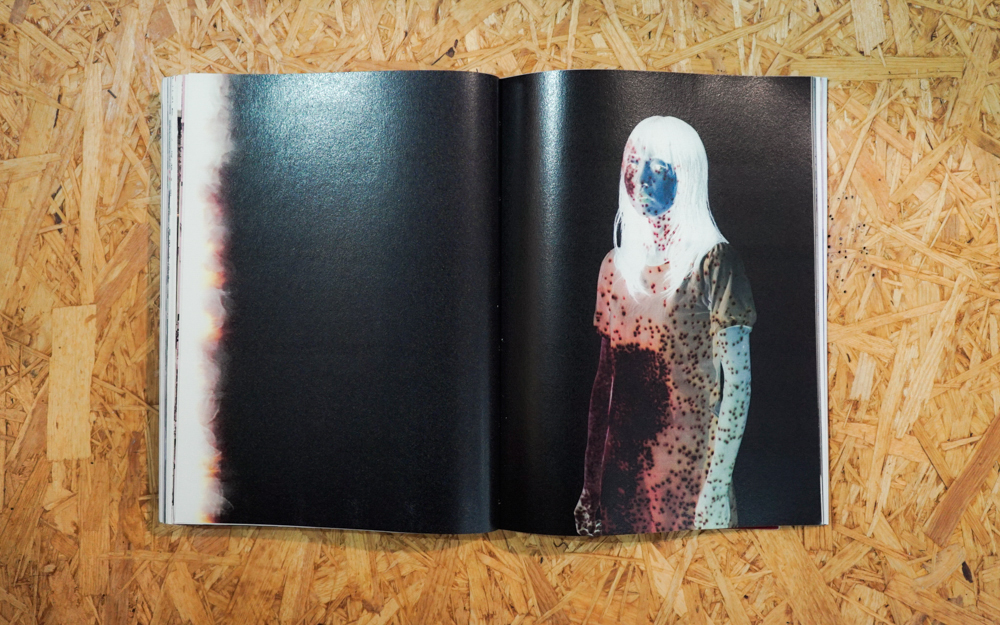

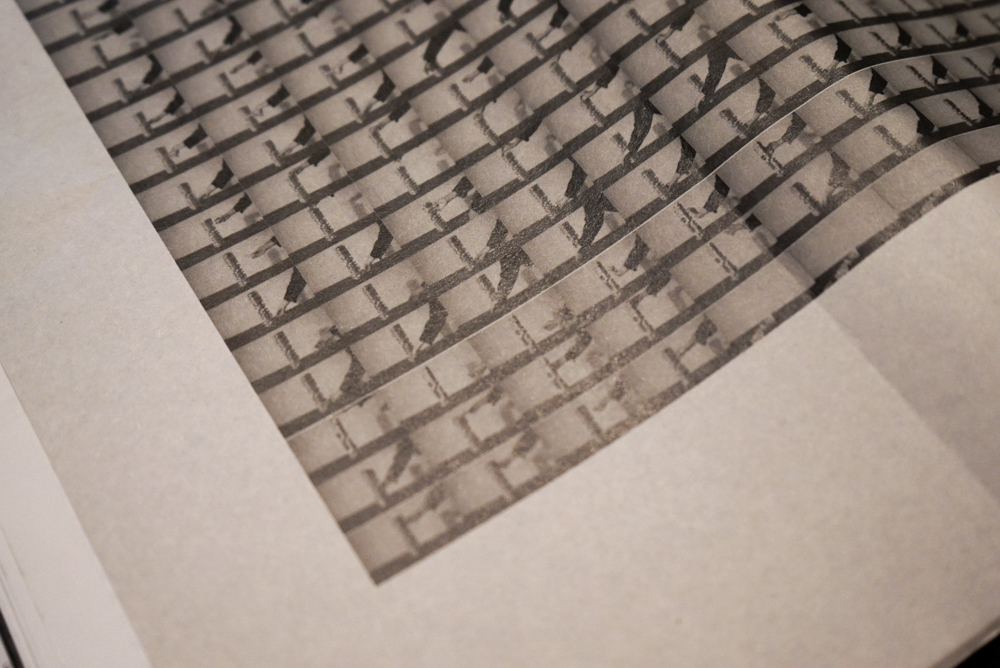

Our psyche is sometimes deprived of its life by the “mind virus” which affects it. Since Goethe published “The Sorrows of Young Werther” in 1774, suicides imitating the protagonist of the novel occurred one after another among young people. This work has a history of being banned in several countries as a result. Love suicides became frequent in the early 1700s in Japan as well, due to Joruri plays such as “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki” by Chikamatsu Monzaemon, and the shogunate forbade its performance. At the time, the chain of love suicides spreading almost like an infectious disease was called the “love suicide tuberculosis”. History repeats itself, and emotions almost similar to an admiration for suicide continued being fueled afterwards by the suicides of Misao Fujimura, Ryunosuke Akutagawa and the Sakatayama double suicide. It spreads like a virus throughout society, from the brain of one person to another.

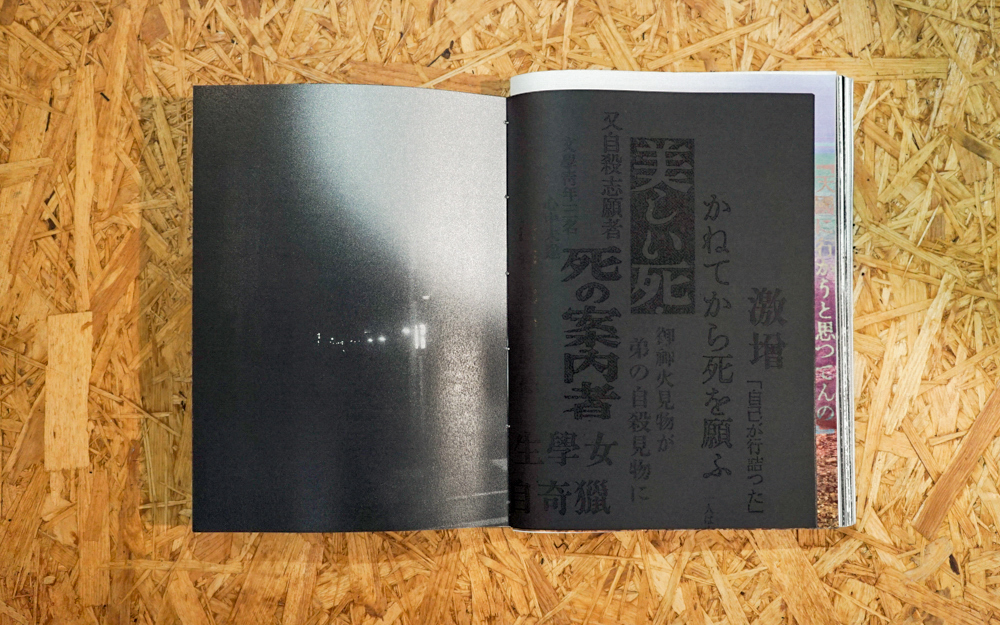

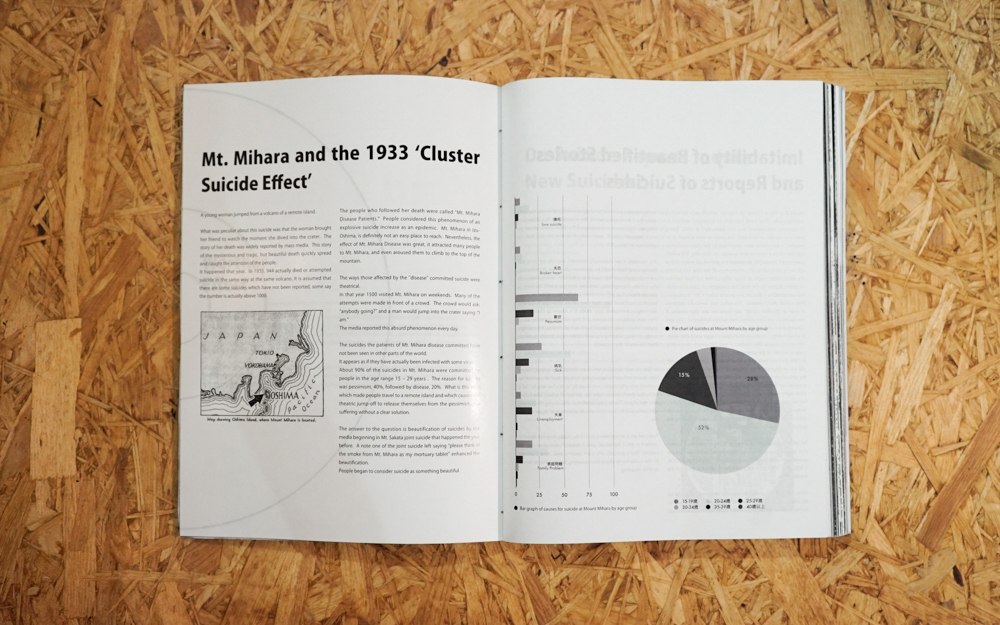

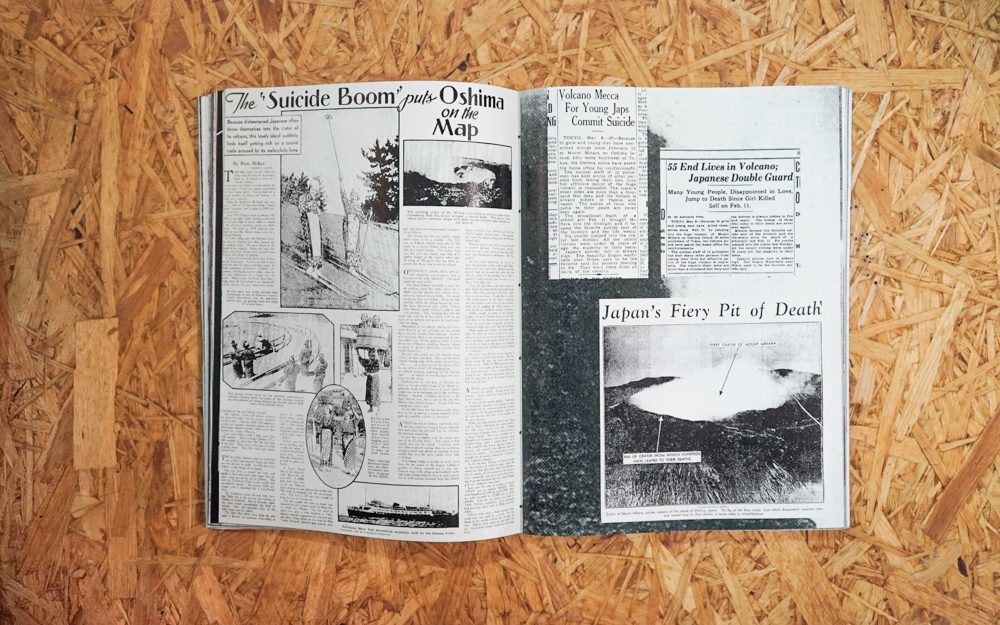

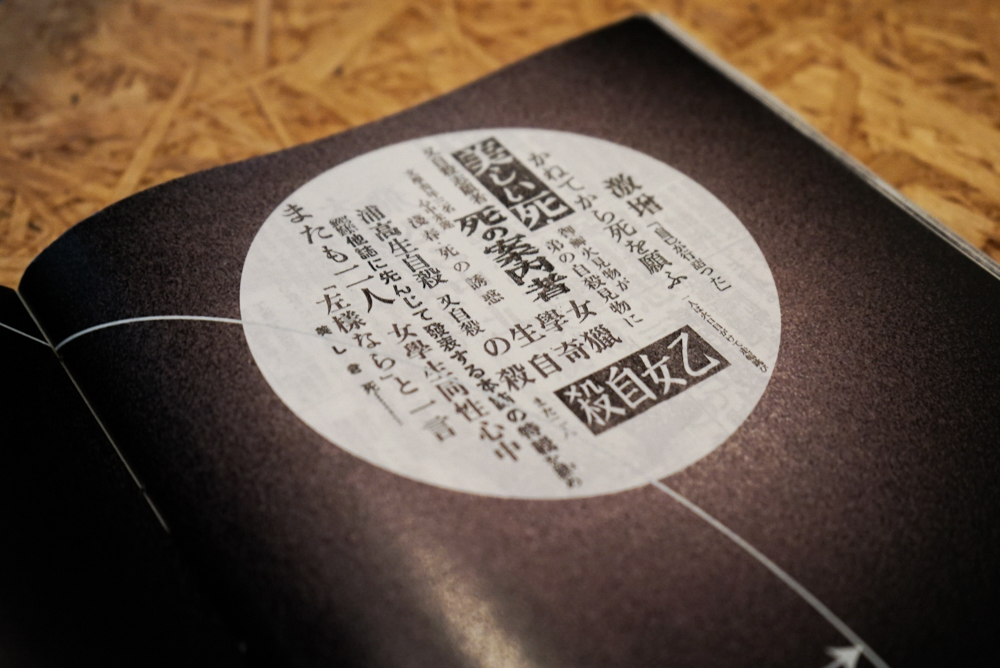

In 1933, a suicide which occurred on Mount Mihara in Oshima was reported as sensational by the media at the time. It being a suicide by a beautiful woman, her not following any attendant, her words that she’s going to heaven, and the mystery of disappearing into smoke without leaving a corpse were all things which gathered much attention from society. As a result, there were 994 attempted suicides in a similar manner in one year on Mount Mihara. The proportion of people under 30 years old was no less than 95%. The number of tourists increased by 50% from the previous year, and 150,000 people came to see the site of the suicide during the course of a year. Along with that, this place created a “suicide spot” image, and attracted many people wishing to commit suicide the following 3 years or so as a result.

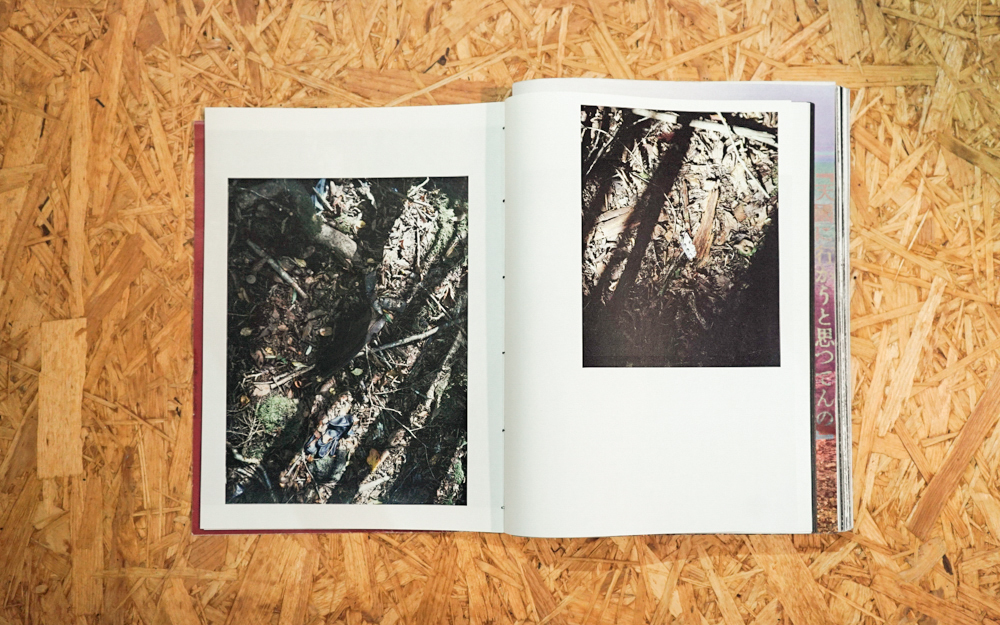

Mount Mihara is now no longer considered a suicide spot, but the most famous suicide spot in the world is in Japan. It is the Aokigahara “Sea of Trees”. They say that this place became recognized by the world as a suicide spot since “The Tower of Waves”, a novel by Seicho Matsumoto, was published in 1960. Suicides were being carried out there occasionally even before, but the scene of “a beautiful woman on the verge of suicide in a sea of trees” depicted by the novel and the movie released in the same year must have been seen by some people as an attractive option.

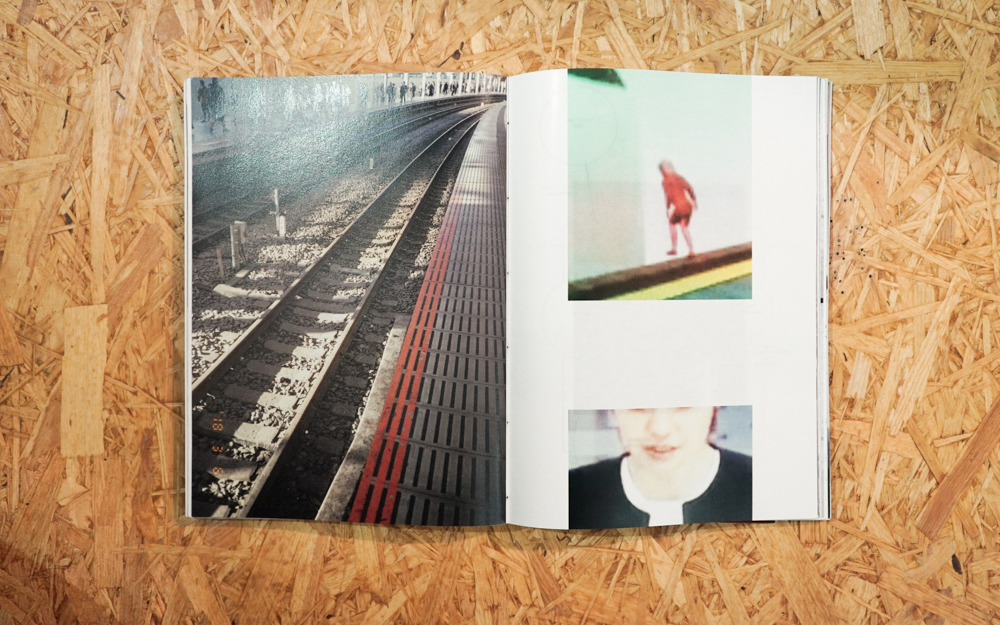

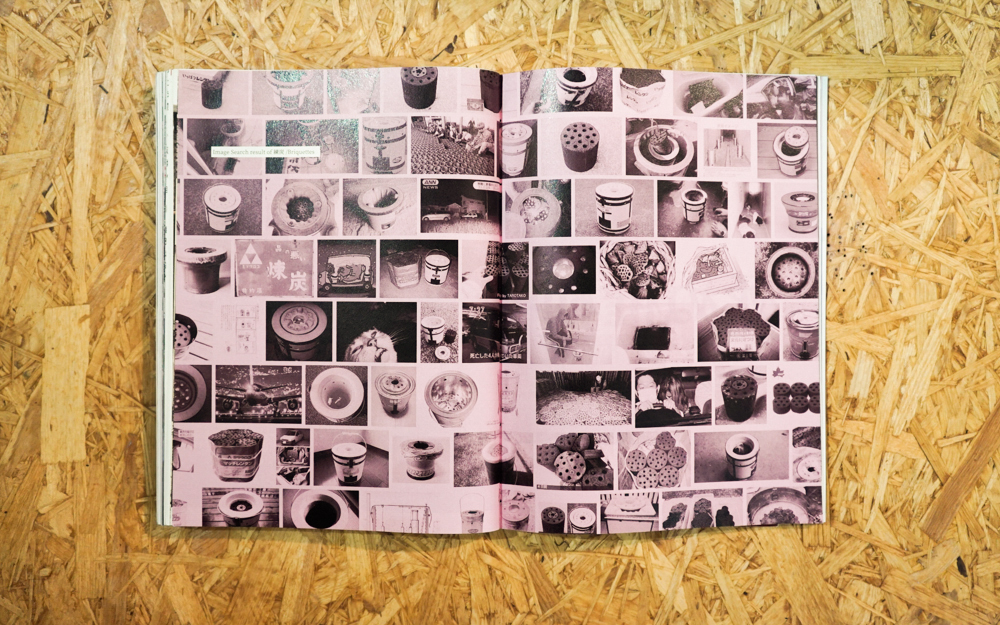

In 1974, sociologist David P. Phillips named the phenomenon which causes these imitative suicides “the Werther effect”. In 2000, WHO published “How to report suicide cases in ways which prevent suicide”. In other words, a guideline on suicide media reporting. Among the items listed in the guideline as those which may “cause a chain of suicides” are posting photographs and wills, and reporting details concerning the location and method, but, from that time to the present age, things such as these have been reported numerous times for suicides of famous people and news-hook suicides which gather people’s attention. The suicide of Yukiko Okada caused the “Yukiko Syndrome” through its media reports, and the Shin-Koiwa Station became a suicide spot through media reports and Internet memes. The people committing suicide have no intention of creating followers – they are created by those who are left behind.

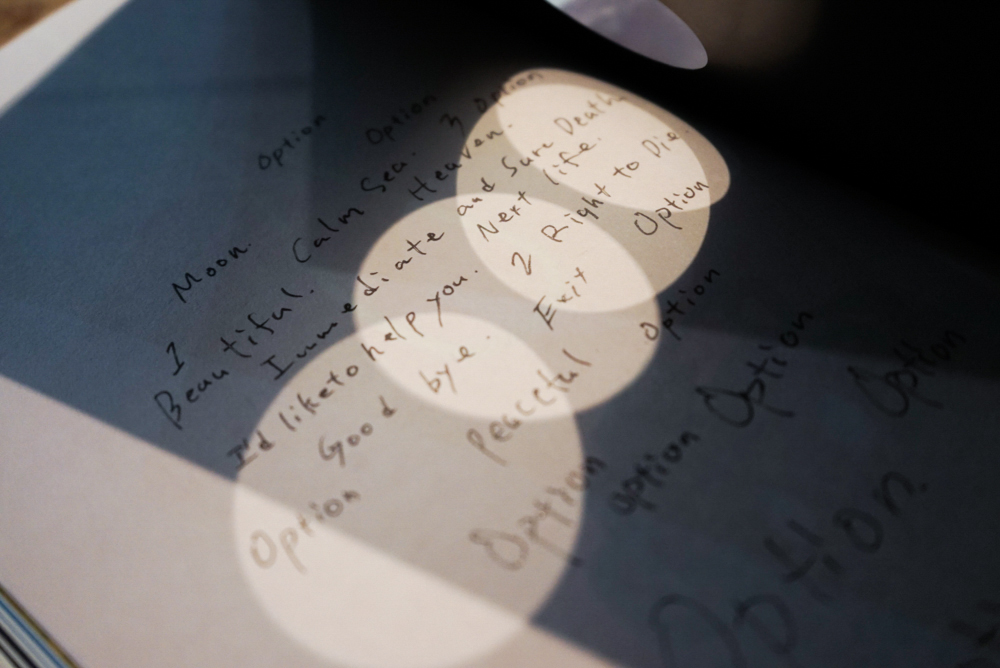

Words and tales accompanying suicide change in form and spread, influencing people’s behavior when they face difficulties. “I’ll repent by dying”, “We’ll be bound in Heaven”, “I only bring trouble to my family”, “I’m better off dead”, “I’ll make you regret”, “I’ll be reborn”, “The meaning to life”, “I have a right to die”, etc. Are they maybe only repeating words they have heard somewhere? Even if it is not so, is suicide really the only path left? While the brain matures, young people are likely to behave impulsively, and the majority of imitative suicides are committed by young people. Furthermore, they are now closer to the Internet than other age groups, and they have a sense of familiarity with the voices of the invisible crowd. They are suitable prey to the “suicide mind virus” which makes people think of suicide and wants to make them commit it. Are the people using the word “die” on a daily basis aware of its power?

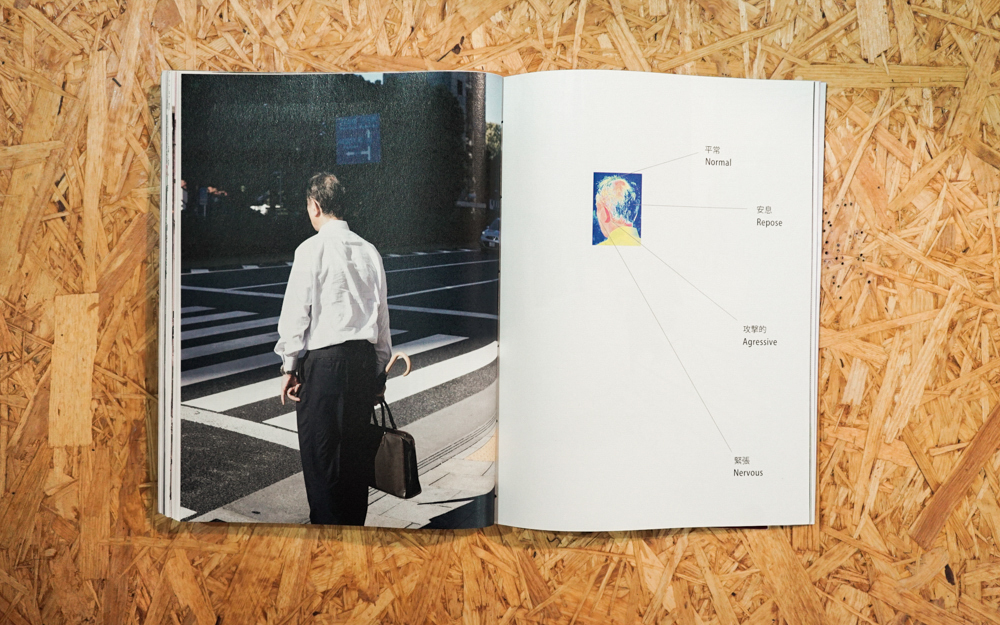

As with the Internet, the advancement of technology enables the analysis of emotions from images in order to create a suicide prevention technology, it aims to eliminate suicidal wishes using brain implants, and will soon distribute death by euthanasia devices made with a 3D printer. Now, which of these is attractive? When mentally unstable and in the gap between “I want to die” and “I want to live”, the “inevitable end” death lets us see presents a great temptation. Japanese people sometimes think of desperately wanting to live as something shameful, but desperately wanting to live is never shameful.

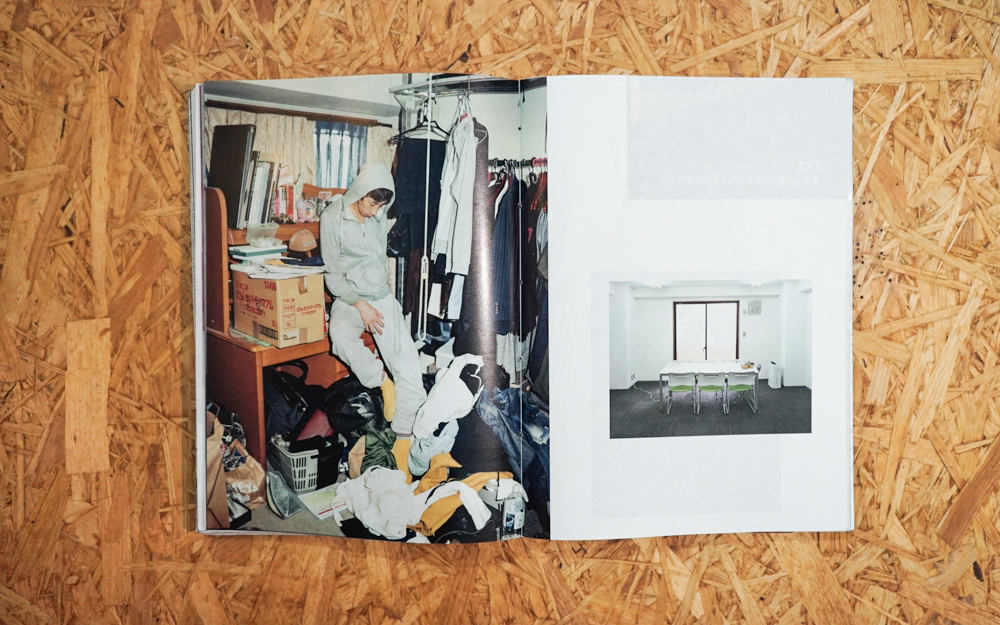

It is the pain that is the problem. Mental, physical, economic, people only want to escape from pain. They are not looking for death. They are looking for liberation from pain. It is just that death presented itself as a simple and clear method of liberation. I’m not saying that dying is necessarily a bad thing, but there are no possibilities if you are not alive. Through this project, I’m considering how we are influenced by people other than ourselves, and whether recognizing the enemy called “the suicide mind virus” may become a vaccine for it.

Kenji Chiga

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom

©︎Kenji Chiga / The Suicide Boom