Reflections on Seeing and Space — Curatorial Notes on After all (Text: Yumi Goto)

As part of a recent talk event, I had the opportunity to share some reflections as a curator on how exhibition spaces interact with the viewer’s body, memory, and emotions. What follows is a written record of those thoughts—an attempt to articulate the questions and explorations that emerged at the intersection of exhibition design and curatorial practice.

As part of a recent talk event, I had the opportunity to share some reflections as a curator on how exhibition spaces interact with the viewer’s body, memory, and emotions. What follows is a written record of those thoughts—an attempt to articulate the questions and explorations that emerged at the intersection of exhibition design and curatorial practice.

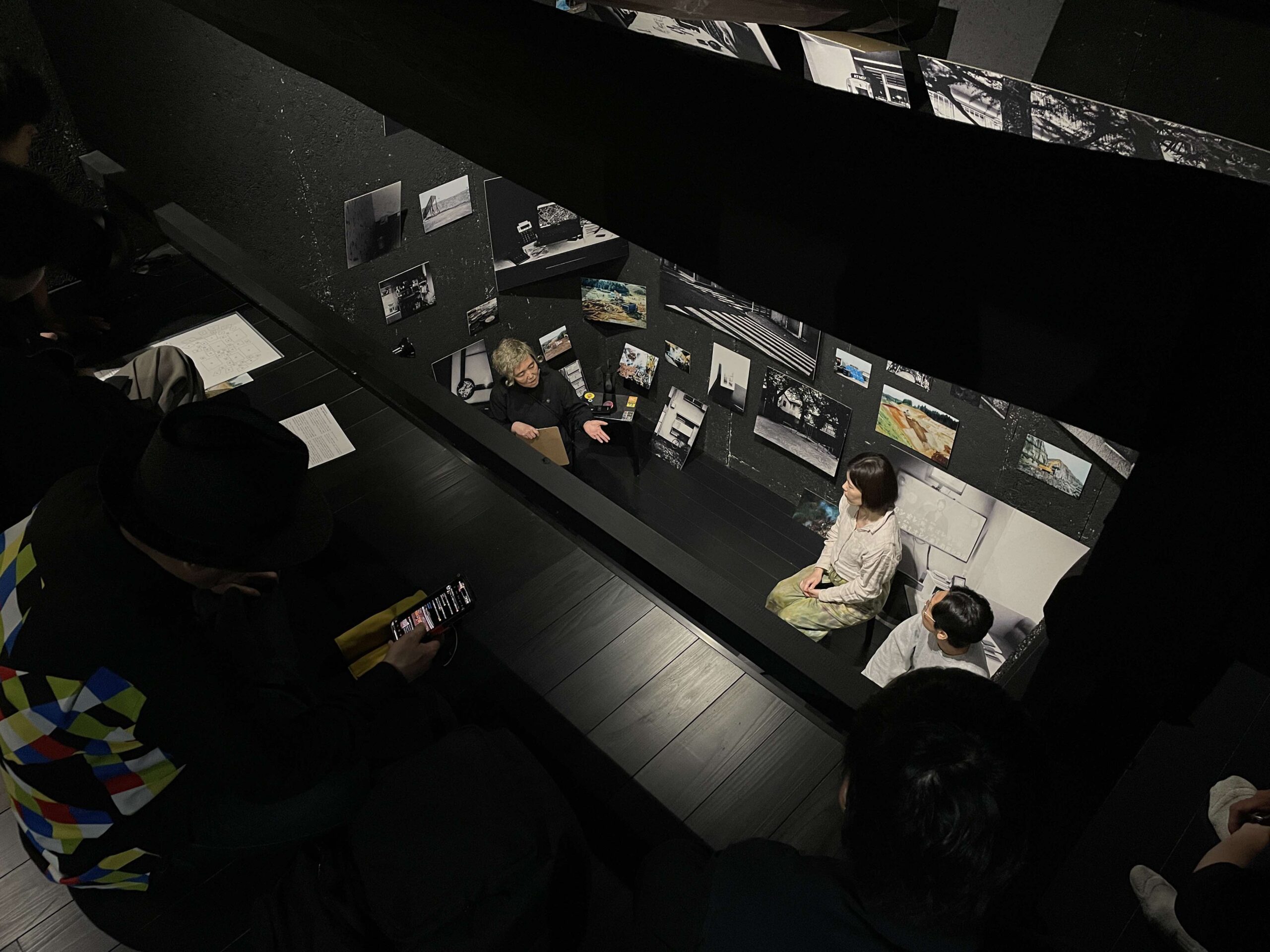

The installation features photographs by Kenji Chiga and Maki Hayashida, arranged within a structure that varies in height and depth. These spatial variations subtly guide the gaze diagonally, while also revealing shifting dynamics between the subjects and their representations. At times, elements that were once visible become obscured; other times, new details emerge—creating a composition where the works seem to draw the viewer into a dialogue, rather than simply being observed.

The installation features photographs by Kenji Chiga and Maki Hayashida, arranged within a structure that varies in height and depth. These spatial variations subtly guide the gaze diagonally, while also revealing shifting dynamics between the subjects and their representations. At times, elements that were once visible become obscured; other times, new details emerge—creating a composition where the works seem to draw the viewer into a dialogue, rather than simply being observed.

A singular phrase, “The future depends on what we do now,” is displayed within a stark, life-sized domestic setting. Though familiar and comfortably phrased, within the exhibition’s context this language begins to acquire new layers of meaning. It acts as a provocation, revealing how internalized social norms and accepted “truths” can shape individual value systems.

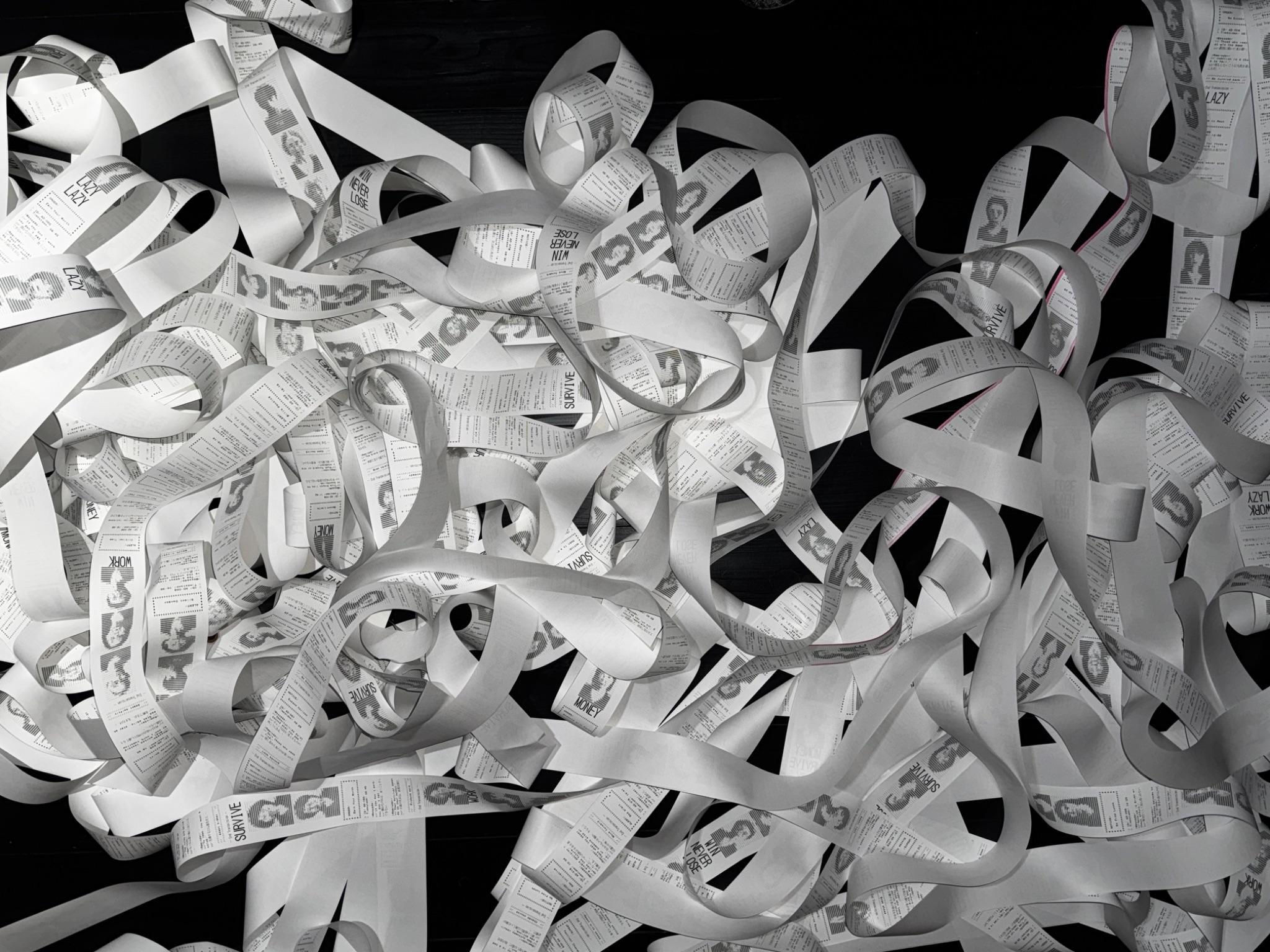

A singular phrase, “The future depends on what we do now,” is displayed within a stark, life-sized domestic setting. Though familiar and comfortably phrased, within the exhibition’s context this language begins to acquire new layers of meaning. It acts as a provocation, revealing how internalized social norms and accepted “truths” can shape individual value systems. In the upstairs room, a machine installation by Chiga prints endless receipts, each bearing motivational slogans accompanied by unsettling ASCII-art faces. These messages—ubiquitous and persuasive in daily life—are rendered absurd and menacing through repetition, exposing the violence of commodified value systems and behavioral control.

In the upstairs room, a machine installation by Chiga prints endless receipts, each bearing motivational slogans accompanied by unsettling ASCII-art faces. These messages—ubiquitous and persuasive in daily life—are rendered absurd and menacing through repetition, exposing the violence of commodified value systems and behavioral control.

This exhibition does not merely display photographs on walls. The space itself becomes part of the work. It is only through bodily movement that the full meaning of the pieces emerges. As a static medium, photography is given dimensionality and temporality through its spatial and experiential articulation.

This exhibition does not merely display photographs on walls. The space itself becomes part of the work. It is only through bodily movement that the full meaning of the pieces emerges. As a static medium, photography is given dimensionality and temporality through its spatial and experiential articulation.

In preparing this show, I encountered a particularly insightful essay that helped frame these ideas: “Exhibition Design and the Relationship With the Spectator” by Brazilian scholar Renata Perim Lopes. The essay explores how early 20th-century figures like El Lissitzky and Herbert Bayer envisioned exhibition spaces as multisensory, participatory environments. Their work emphasized the role of spatial navigation, physical posture, and perception in shaping the audience’s experience.

In preparing this show, I encountered a particularly insightful essay that helped frame these ideas: “Exhibition Design and the Relationship With the Spectator” by Brazilian scholar Renata Perim Lopes. The essay explores how early 20th-century figures like El Lissitzky and Herbert Bayer envisioned exhibition spaces as multisensory, participatory environments. Their work emphasized the role of spatial navigation, physical posture, and perception in shaping the audience’s experience.

Text and Composition: Yumi Goto (Curator, RPS KYOTO PAPEROLES)

Exhibition Information

Title| After all

Artists| Kenji Chiga, Maki Hayashida

Venue| RPS KYOTO PAPEROLES (603 Oimatsu-cho, Kamigyo-ku, Kyoto)

Dates| April 12 (Sat) – May 11 (Sun), 2025

Hours| 13:00 – 19:00

Admission| Free