Reflecting on the Exhibition: On Manami Uetake’s “The end’s approach comes over my mind as clouds cover the light” by Yumi Goto (Curator, Reminders Photography Stronghold)

When I first encountered this work, what struck me most was the artist’s sincere attempt to grapple with two intertwined questions: How do we speak about what we would rather not speak about? And how can such things be made visible and accessible to others through a work of art?

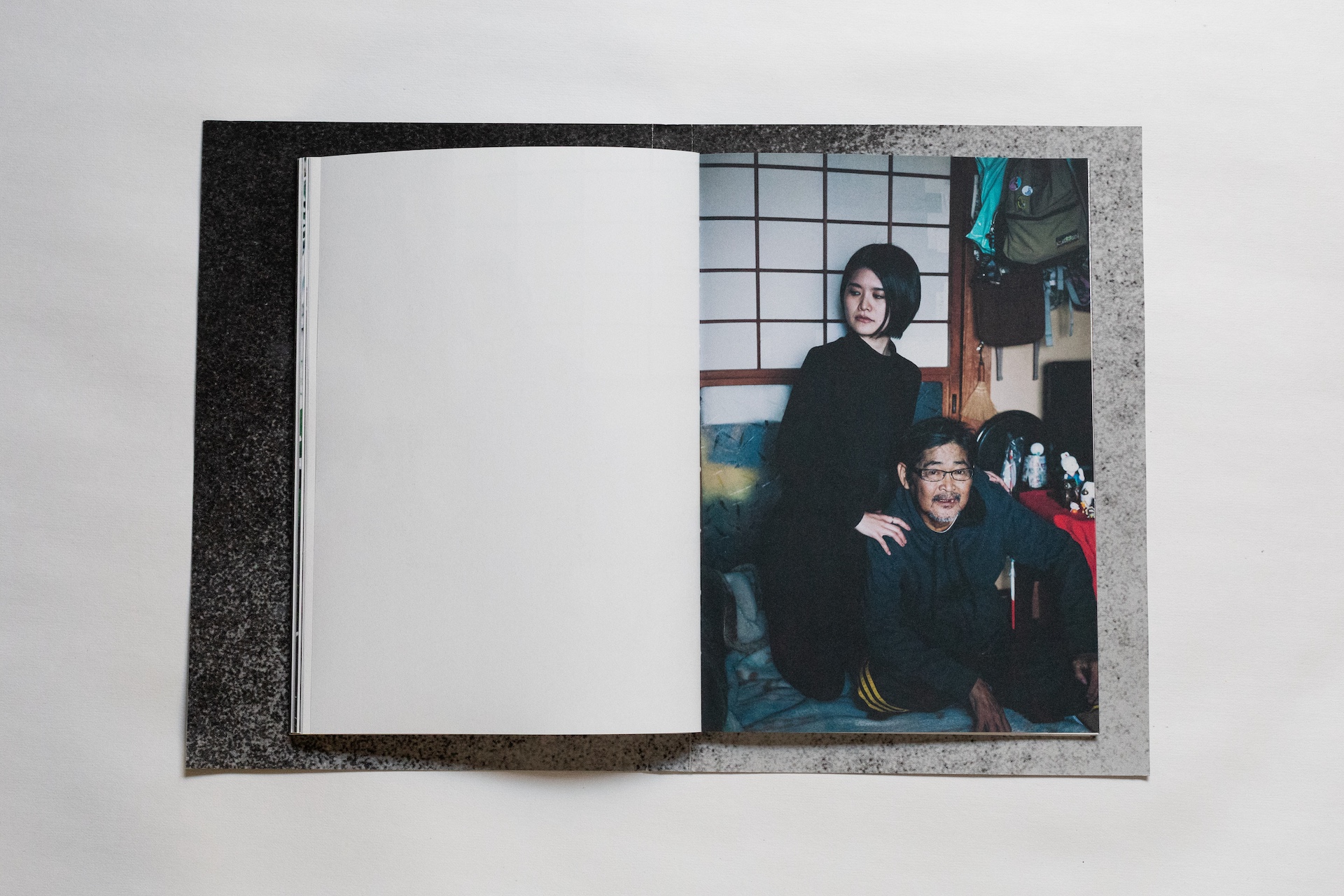

In this piece, Manami Uetake turns her gaze toward one of the most intimate and difficult subjects to address—her family, and more specifically, her father. Precisely because of this closeness, the layers of emotion are deeply intertwined, and to externalize that experience through artistic expression is an act that inevitably involves exposing oneself—often painfully so.

Presenting such private memories as a public artwork also requires transforming personal experience into something that can be shared and understood by others.

This process, I believe, inevitably demands a negotiation between emotional editing, reconstruction of memory, and an awareness of the role of silence in storytelling.

By “emotional editing,” I mean the process of creating necessary distance from one’s own feelings in order to reexamine them, and to make thoughtful decisions about what to reveal, what to withhold, and how to structure emotional truths in a way that maintains integrity without becoming too private or overwhelming for the viewer. Especially when working with themes such as family and death, the emotional weight can easily distort the balance of the work if left unexamined.

“Reconstructing memory” refers to the recognition that memory itself is fragmented, ambiguous, and often unreliable. Memories shift and warp over time, sometimes through willful forgetting or selective recall. Uetake engages with these fragile threads—photographs, audio recordings, remembered conversations—and weaves them together into a narrative that doesn’t seek completeness, but rather opens space for connection and re-understanding. The act is not only one of reconstruction but of reconnection.

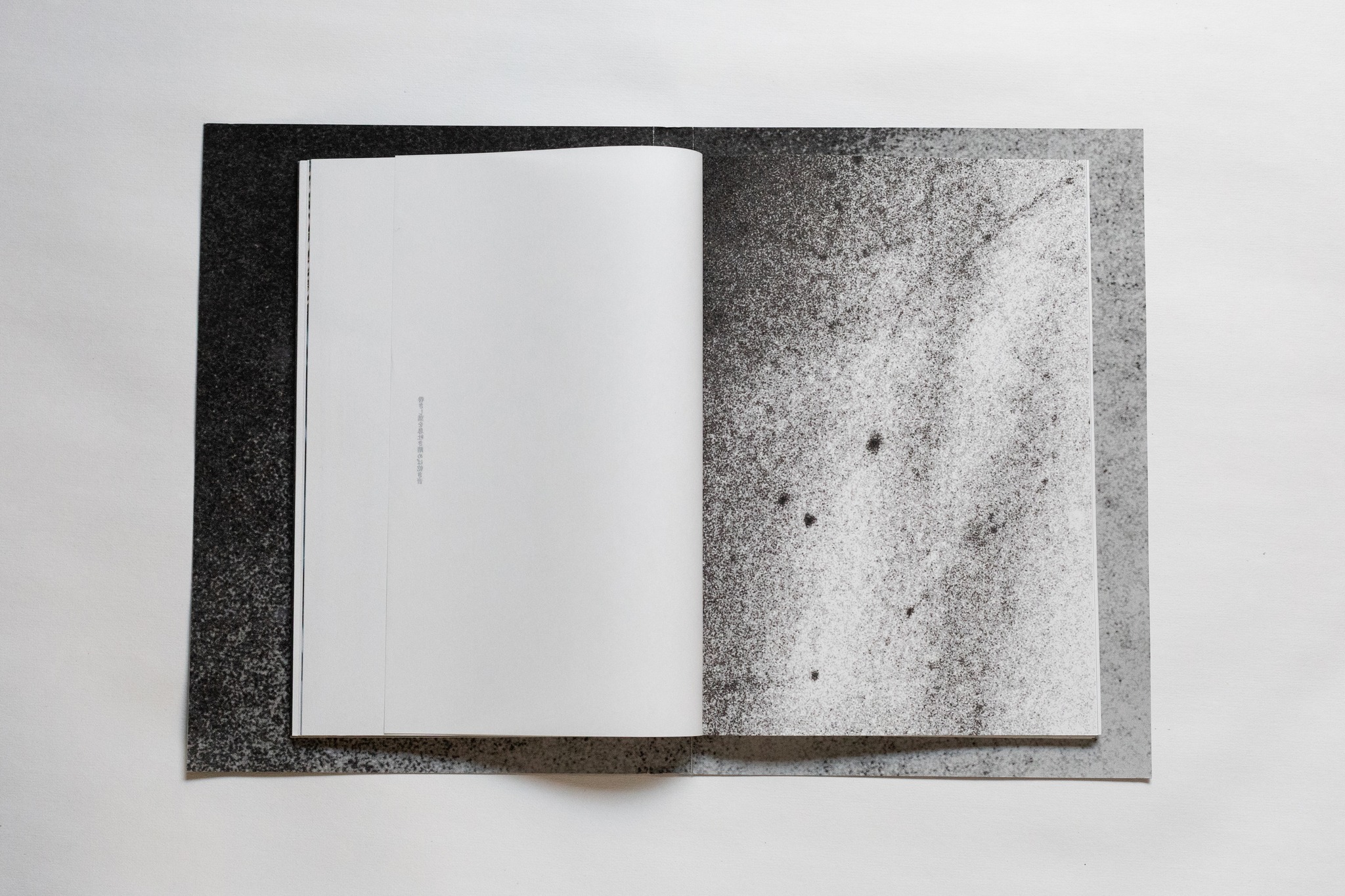

The role of silence in storytelling is also a conscious compositional element—what is left unsaid, untouched, or off-frame.

Particularly in works that deal with personal memory or family relationships, articulating everything can risk oversimplification or overexposure.

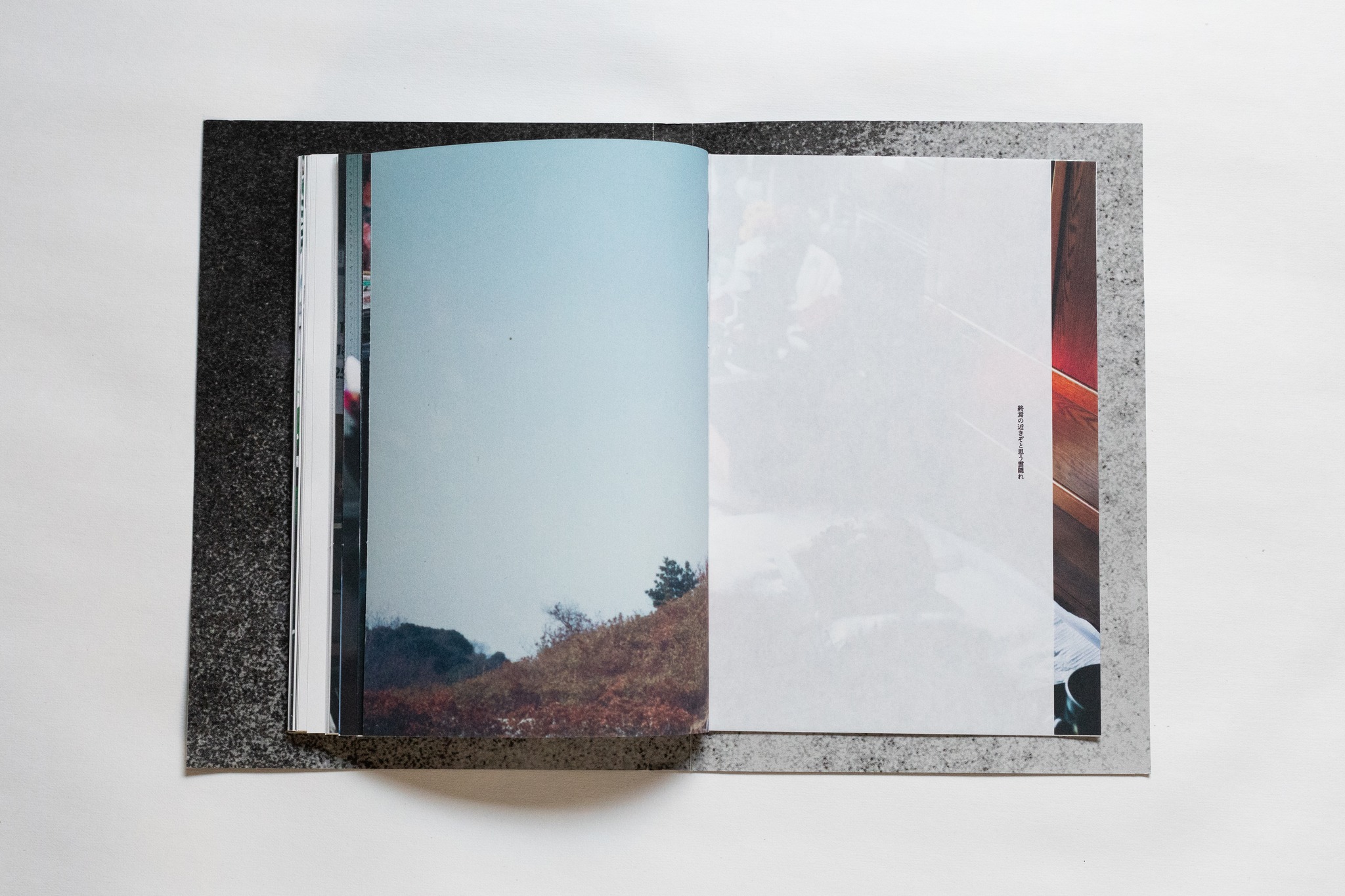

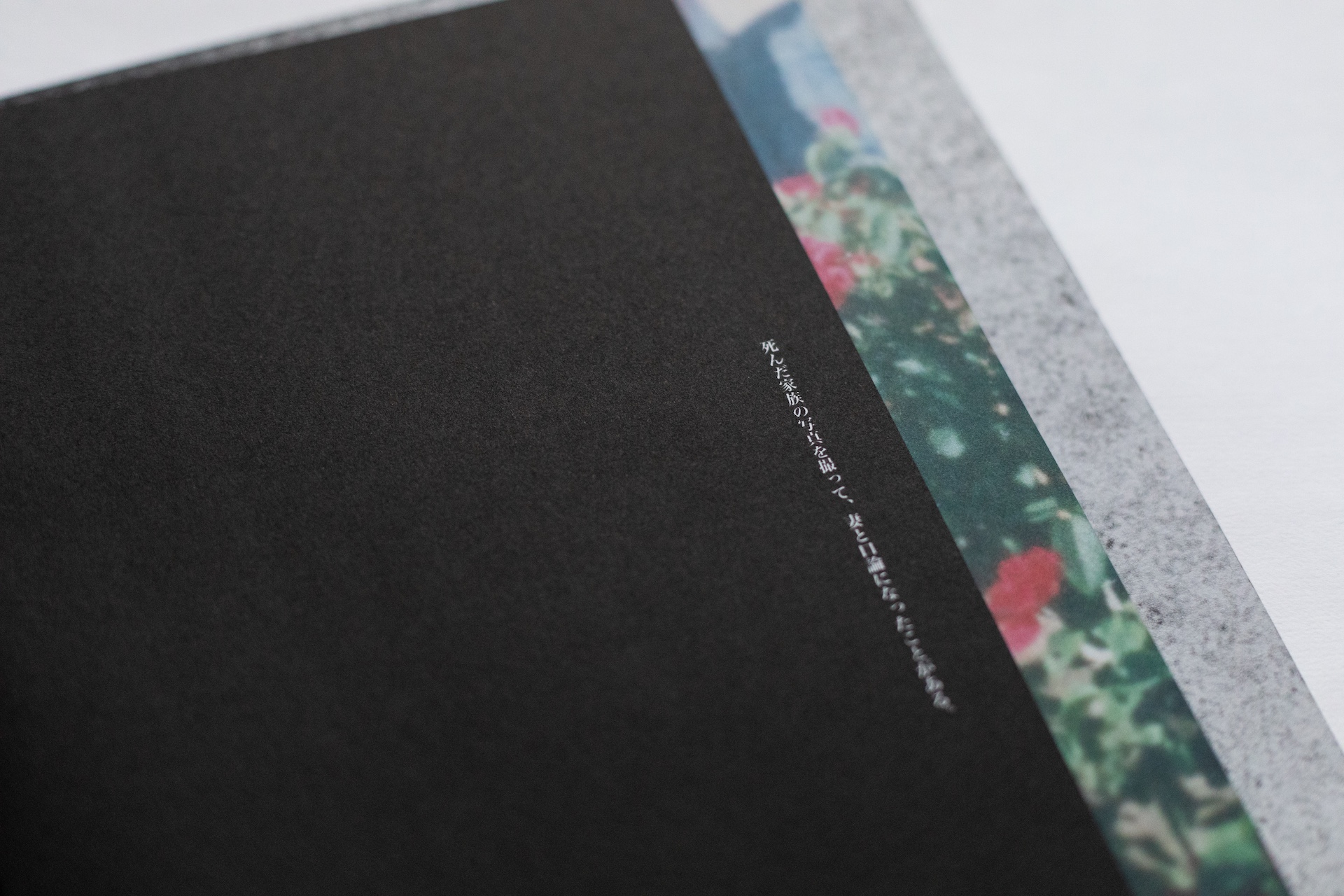

Uetake preserves spaces of silence within her work: the pauses in reconstructed monologues with her father, the asymmetry of phrases across the pages, the lingering presence of a haiku alongside an image.

These silences are not voids, but quiet invitations—spaces in which the viewer’s own memories and emotions might settle.

In this way, silence is not an absence but a structuring presence—shaping how the story is perceived and felt.

Throughout her practice, Uetake has consistently engaged with the question: Is it truly possible to understand another person? In this work, she focuses not on distant others, but on the closest and most complicated: her own family. Her father’s haiku, his skin, his voice, and their shared photographs become the raw material through which she attempts to traverse the space between memory and imagination. It is not the certainty of understanding, but the sincerity of the attempt—that unresolved, reaching gesture—that forms the quiet core of this book.

What I find remarkable about Uetake’s work is its delicate and honest balance. She remains close to her own emotions, yet always reshapes them into a space that remains open to others. That quiet courage—and the craftsmanship behind it—is what gives this work its depth.

What left a lasting impression on me was the complex narrative layering produced by the intersection of photographs and text. Originally a photographic work, the addition of haiku found on her father’s old social media posts and the inclusion of their interwoven monologues expanded the work’s emotional and narrative range. These exchanges—alternating across recto and verso—form a dialogue that transcends time, and perhaps even life and death. Through them, Uetake interrogates what it means to photograph, to preserve, and to remember.

What left a lasting impression on me was the complex narrative layering produced by the intersection of photographs and text. Originally a photographic work, the addition of haiku found on her father’s old social media posts and the inclusion of their interwoven monologues expanded the work’s emotional and narrative range. These exchanges—alternating across recto and verso—form a dialogue that transcends time, and perhaps even life and death. Through them, Uetake interrogates what it means to photograph, to preserve, and to remember.

In the physical exhibition, too, each element—photograph, text, margin, layout—functions not in isolation but in sync, like breath. The space itself invites the viewer’s body and memory into participation, transforming the act of “viewing” into something active, embodied, and deeply personal.

This project has led me to reconsider what photography can be, what it means to speak, and how memory takes shape. And I believe that the experiences and emotions of those who engaged with the book and exhibition have also quietly entered the work—becoming part of its evolving presence.

Yumi Goto (Curator, Reminders Photography Stronghold)

Although the exhibition has ended, Manami Uetake’s artist book “The end’s approach comes over my mind as clouds cover the light,” which she printed and hand-bound herself, is now available for order.

This is a special edition of only 65 copies, reflecting the age of her father at the time of his passing.

For details and ordering, please visit the link.